Dear Lisa,

I have an experience that I want to make into a short story, but I don’t really know how. I feel like when I try my story turns out like the ones my uncle tells at Thanksgiving that end in an awkward silence punctuated by “That’s great, John.”

What am I doing wrong?

Thanks,

Amy

Hi Amy,

Your question made me laugh—I think we might share an uncle! If yours is anything like mine, he is probably recounting a series of events and failing to connect them together to arrive at some point. Kind of like when someone tells a joke but forgets to set up the punch line. The listeners are waiting for the reason this story is being told, and it never arrives.

Before you consider with any seriousness the information I’m about to give you, get your experience on paper, just as it sounds in your mind. Don’t worry whether it’s good—it’s only a starting point.

Once you have a draft, you can start looking at it’s plotline.

What is a plotline?

At its most basic level, a good short story has a point, called a plot line, a compelling character story (called a character arc), both told from an interesting point of view (or POV). Your question is about plotline.

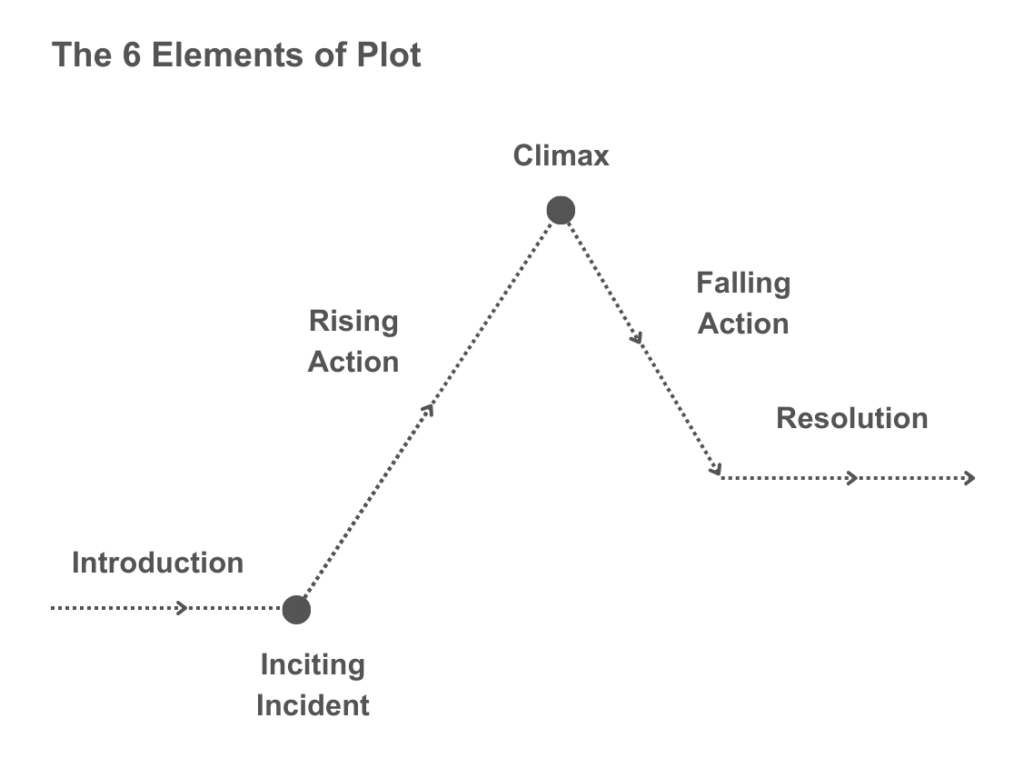

The simplest plotline begins when a character is faced with a problem that pulls them out of their ordinary life and sets them on the trajectory of the story, ultimately toward resolving the problem. In other words, the plotline should do its part to engage the reader, compel them to keep reading through the resolution, and satisfy them at the end. To talk about how this works, I separate the plotline into six foundational elements (some editors use more, others less): the introduction, the inciting incident, the rising action, the climax, the falling action, and the resolution.

If this sounds familiar, you might also remember this diagram:

It shows the plotline as it would look if you could draw it on paper. It is easy to see here how each element is connected to the next, but it takes examining an actual story to see the function of each element and how they work together to create the plotline.

Nursey rhymes and fairy tales are great examples of very simple plotlines. Since we’re all probably familiar with “The Three Little Pigs,” we’ll use it as our example.

Introduction

Once upon a time, there was a little pig building a straw house in the middle of the forest. He built the walls, and the roof, and thatched together a sturdy door. When he finished, he went inside.

The introduction’s purpose is to establish the setting, the character, and the character’s status quo. Done well, the introduction draws the reader into the character’s life laying the groundwork for the change brought on by the inciting incident. This intro does its job very efficiently: we’ve got a pig in a forest, building a house from straw. Everything seems chill. Or does it???

Inciting Incident

Not a moment after he latched his door was there a knock.

“Little pig, little pig, let me in!” the gruff voice of the wolf made the little house shudder.

“No, no, no! Not by the hairs on my chinny-chin-chin!” said the pig.

“Then I’ll huff, and I’ll puff, and I’ll blow your house down.”

And he huffed, and he puffed, and he blew the house down.

The classic calm before the storm! The inciting incident’s job is to pose a problem for the character, and in this case, a point of no return. The little pig must run for his life or die. The inciting incident can be described as the point of greatest change in the story.

Rising Action (1)

The little pig ran out from under the tumbled straw, into the forest, and across a stream to his brother who had built a house of sticks.

Seeing his brother’s alarm, the two ran into the stick house and shut the door.

Sure enough, the knock came. “Little pigs, little pigs, let me in!”

“No, no, no! Not by the hairs on our chinny-chin-chins!

“Then I’ll huff, and I’ll puff, and I’ll blow your house down.”

The pigs felt certain that the sticks would hold up to the gust and stood looking out the window.

The wolf huffed, and he puffed, and he blew the house down.

The points of rising action are often a series of (failed) actions the character takes to solve the problem posed in the inciting incident. Their job is to escalate the tension toward the climax and to give the character (and reader) new information about the plotline (and character). In “The Three Little Pigs” the rising action events involve getting help, sheltering in a stronger house, and the hope that their reinforcements are strong enough to withstand the wolf.

Rising Action (2)

The little pigs ran out from under the rubble of sticks, into the forest, and up a small hill to their brother who had built a house of bricks.

Seeing his brothers’ alarm, the three ran together into the brick house and shut the door.

And just in time. The knock came. “Little pigs, little pigs, let me in.”

“No, no, no! Not by the hairs on our chinny-chin-chins!

“Then I’ll huff, and I’ll puff, and I’ll blow your house down.”

The three little pigs were nearly certain that the brick house would hold up but braced themselves against the door anyway.

The wolf huffed, and he puffed, and he blew as hard as he could. Again, he huffed, again he puffed, but the house stood strong and immovable.

The little pigs gathered at the window and watched the wolf as he panted with rage. Then he crouched to the ground and slinked off into the forest.

The pigs rejoiced in their victory, clattering about the kitchen, gathering a feast to eat.

This story makes excellent use of the rising action with the number of pigs and strength of the shelter increasing with the rise of tension and fury of the wolf. We’re good and ready for the climax now.

Climax

Then all at once, they heard a scraping and scratching at the brick wall at the back of the house, then the soft clicking of sharp claws on padded feet across the shingles of the roof. The three little pigs froze in horror. There were no windows to see, but soon they heard the raspy voice of the wolf.

“Little pigs, little pigs, I’m going to come down the chimney and eat you!”

The three little pigs huddled at the center of the room, shaking and scared. Then the third little pig spoke with all the strength he had, “No you won’t! Not by the hairs on our chinny-chin-chins.”

The wolf laughed and the pigs could hear his claws scrabbling into the chimney stack.

The three little pigs looked at one another and then looked at the feast they had prepared. Without a word, they pulled the enormous soup pot off the stove and set it in the bottom of the fireplace where they lit a blazing fire.

The cackling of the wolf slowly turned to the yelping of an injured hound as he slid down and down the chimney, ever closer to the fire. Then with a splash, he fell into the scalding water.

The climax is the culmination of the increasing urgency of the problem posed at the beginning, the tension build by the rising action, and the desperation of the character to prevail. It is one of the main elements in the story where the character arc and the setting come together (sorry, I know I said this was going to be about plotline). The job of the climax is to present the solution to the problem, but to do so in a way that challenges the character to not only solve the problem, but to overcome whatever internal barrier has been holding them back. This often means a contrast between the character’s lowest point, and their greatest triumph, making the climax the point of greatest tension.

In the case of “The Three Little Pigs” the pigs must not only use their number and the strength of their shelter to prevail over the wolf, but their cunning as well. I intentionally chose a story where the characters arcs remain in the background, but you can see how even a little character can elevate the plot when the third pig pipes up.

Resolution

The third little pig put on the cover. They boiled up the wolf and all three ate him for supper.

And so, the three little pigs lived happily together safe and sound in their sturdy house of bricks.

Like most fairy tales, “The Three Little Pigs” ends efficiently. But it does it’s job by showing us how the characters reintegrate into their status quo newly transformed by their recent adventure.

Next Steps

Now that you have the basics of plot under your belt, you can take another story you’re familiar with and plot it out like we did above. Or, if you ready, you can start to compare what you’ve written with the six elements. As tedious as it is, it can be helpful to break your story down stories into point form and fit them under the headings. This helps you make sure that all of the plot points are present and doing their jobs.

And before long, your brain won’t just stop at experiences. It will automatically turn your experiences into plotlines, thinking of creative ways to build tension, or resolve a tricky problem.

A note on complex plotlines

As the story generating process becomes second nature to you, you’ll start to notice that not every story has defined moments for every element. Maybe the story starts with the inciting incident and the setting, character, and status quo are integrated into the body of the story instead of set out in an introduction. Or maybe the author has found a clever way to tie up all the loose ends within the climax, so there is very little resolution. At this point, you can thinking of addressing the plot points, rather than writing them.

Good luck on your story writing journey! If you have more questions, I’m always here.